We spoke to Jason Li, Associate and Charles Corley, Director of Organisational Development at M Moser Associates about how virtual design and construction complements an integrated project design and delivery approach.

Over the past fifteen years, M Moser, a global AEC firm with an extensive track record in workplace design and construction, has used SketchUp not only for design and conceptualization but as a vital communication tool throughout the project delivery process.

What does the term “VDC” mean to M Moser?

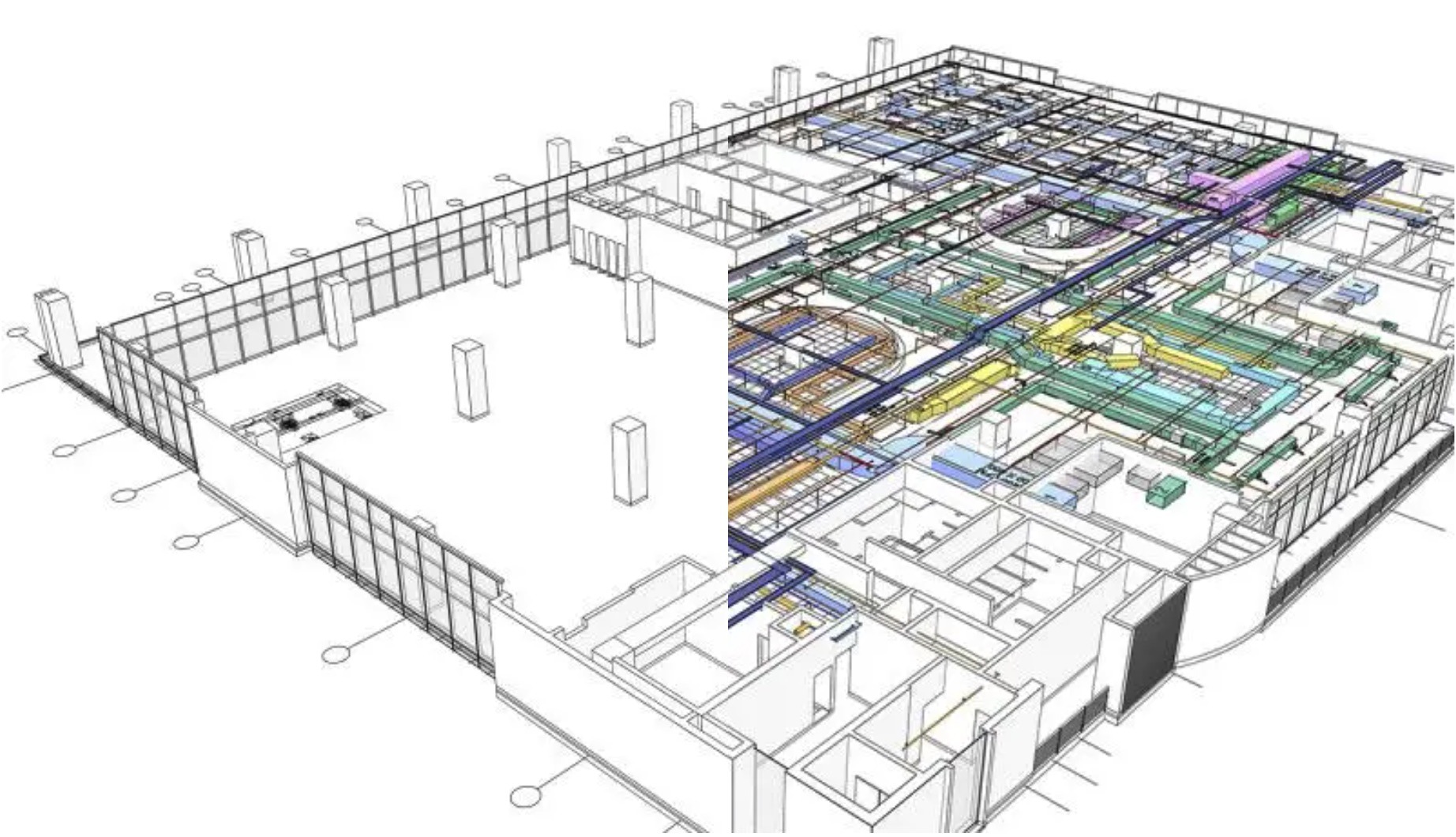

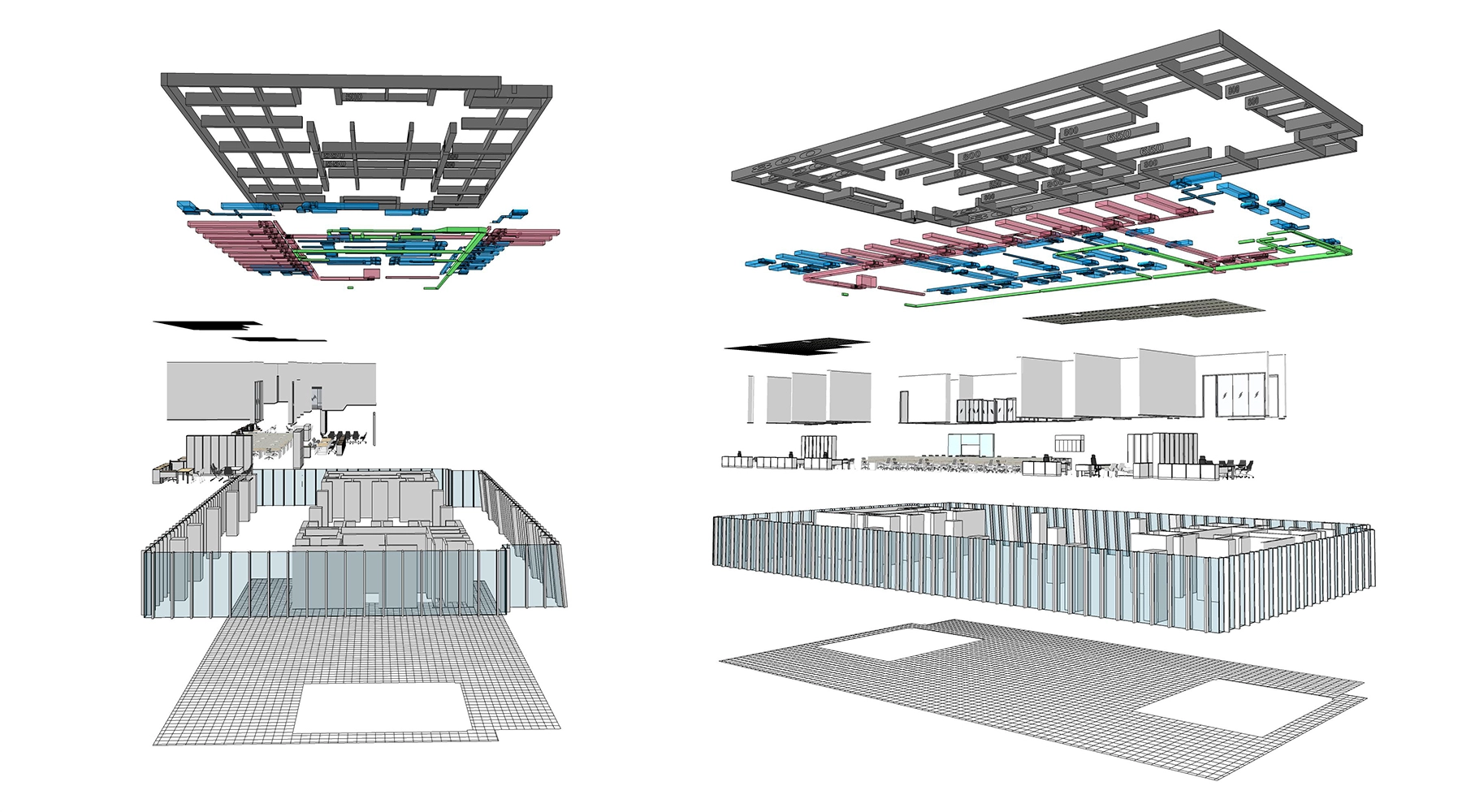

Charles: It’s Virtual Design and Construction and by that we mean an entirely constructible 3D modeling workflow that empowers any stakeholder to understand and participate in a project. We can create a working virtual environment that makes everything clear to all project participants regardless of training or experience. Rather than relying on a highly coded or flat and disassembled, abstract set of documents, a visual reference is universal. A desk looks like a desk; a wall looks like a wall. You don’t need an expert interpreter of construction documents in order to understand fully and collaborate.

M Moser prefers to own as much of the responsibility on a project as possible. The best case scenario is we’re the designer, engineer, purchaser, and contractor. The deliverable, if you will, is the completed project. Throughout all of our offices worldwide, we use virtual design and construction out of a need to have everybody understand each other. We have an array of cultures, understandings, and backgrounds in construction. We want people to engage meaningfully and get the best out of each other’s contribution and expertise by constructing a project in SketchUp well before reaching the site. VDC is a communication tool that gets everybody on the path to the right result.

What types of projects do you focus on as a business?

Charles: We design and build workplaces. Not only corporate offices but corporate campuses, laboratories, private hospitals, private education facilities, and workplaces of all types. You name it, we’ve done it.

Using a nimble tool like SketchUp is also extremely important as these types of projects can be ever-changing. With more traditional building projects you have to nail down things well before construction for many reasons such as permitting, structural calculations, and ordering materials. But workplaces, even extremely large ones, can remain fluid in design. Even the size of the premises could change considerably. Departments can move around. Mergers and acquisitions could change the whole landscape of the office.

“The flexibility of SketchUp allows the entire team, including clients, specialists, and contractors to keep up.”

Is there anything unique about the way you operate?

Charles: In some ways, we’re sort of the enfant terrible. We’re radical about change and are constantly evolving the way we think about construction information. Where many firms are steeped in more traditional documentation, we’re trying to make any record of construction information a by-product of the real collaboration and 3D work.

We don’t want to send out stacks of documents to people who have never seen it before and say, “Go read this and get back to us with a price.” We’d rather have them involved from the very beginning. This means, all the trades, contractors, suppliers, and the client works together in 3D, from concept to completion.

We’re trying to shake the tree were a lot of people don’t want to change. Jason and I have a lot of war stories about how people are incredibly stubborn to change and don’t wish to consider alternatives. We’ve broken down a lot of assumptions like, “You can’t use SketchUp for official documents to send to the government,” or “It’s not accurate enough,” or “We can’t collaborate with consultants using other programs.” These arguments have melted and fallen by the wayside.

Jason: M Moser could be considered quite unique in the industry because our focus is not just on the design. We have to consider the contractors and the building. For many companies, their role ends when they hand over the designs and completed documents, whereas we handover a complete result. And even beyond that, our role sometimes continues into operation and maintenance.

Your designers are charged with producing constructible models. Can they do this on the first pass?

Charles: Not every designer has the experience to really understand construction. They tend to draw the design intent, then they have to work with others to discover what’s possible.

As an example, just recently we had a team discussing an intricate reception counter. The contractor in the room pointed out: “If the table were four inches shorter, we could use off-the-shelf components and wouldn’t have to manufacture any custom pieces.” The designer made the change right then, rationalizing that it wouldn’t really impact the overall look but offered a significant reduction in cost and lead-time. Thousands of collaborative discussions like this occur constantly, many of which wouldn’t be possible in 2D.

Jason: We collaborate on a daily basis; it’s not really like a factory where I do my job and pass to someone else, or “Here’s a stack of drawings, you go and do it.” Projects are realized through discussion and brainstorming. People have different backgrounds and this way we can truly avoid misinterpretations of what the designer intended.

People will always have differing opinions, so does it always go to plan?

Charles: What you would see in our meetings would be a group of people from very different professions, looking at a model being rotated on a large screen. The person leading the meeting is not coming up with all the answers, they’re the “chief question-asker.” The team answers the issues together, marking the live model and taking screen captures. They talk about what needs to change and sometimes even make these changes on-the-fly. It’s very much a team activity.

The notion of success mostly comes from the client but often there are multiple opinions. One might say, “I want to make sure I have the correct amount of meeting rooms;” another person says, “I want to make sure we finish on time;” another, “I want to make sure my boss coming from overseas is happy,” and so on. Those objectives blend together and form the definition of a successful project.

Jason: We’re using VDC as a methodology to ensure designers, engineers, professionals, specialists, and the client can communicate on an equal platform. Our goal is that everybody understands the project objectives to achieve results.

Building constructible 3D models look to be a time-consuming exercise. Is it more efficient than it seems?

Charles: Many would say that you can do something in AutoCAD faster or easier than you can in SketchUp. We have found that is not the case if you use it intelligently. There is often a false understanding of time efficiency. Hand a project to a couple of draftsmen and they may spend hundreds of hours doing the drawings, not taking the time to understand construction. A senior stakeholder would then have to go through each page of the drawings to check them, applying the required 20 years of experience to effectively decipher them. Then there are the perspectives. Visualizers can spend an inordinate amount of time setting up beautiful—but only a limited number of—renders. All those hours really add up.

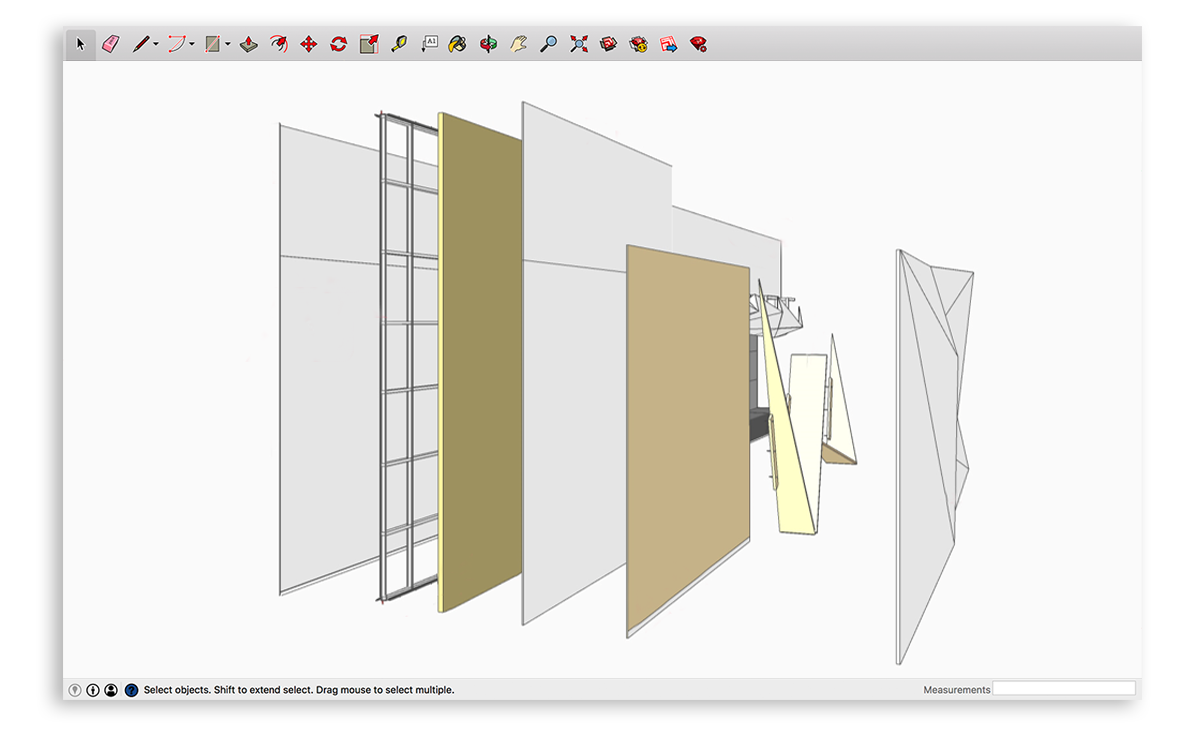

Jason: VDC forces the people who are doing the drawings to think about what they’re building, they can’t just draw lines. With our methodology, the modeler creates everything in SketchUp. Then they split the model into different viewports in LayOut to see right away if something’s not working.

“The key difference is, any changes are immediately echoed through the entire set. Everybody’s job is faster and easier.”

The whole workflow is compressed and more evident to everybody at a glance. Errors are glaring, “Oh, look, this wall is not meeting the mullion correctly.” We can see where buildability is correct and where it is failing, and we can catch it early. There’s also less time spent on visualizations. We can use an extension to quickly do perspectives from any position in minutes instead of hours.

What perspectives can your clients expect to see in the early design stages?

Jason: We do aim to deliver spectacular visuals to help convey our idea. At one time, we had a team of visualization specialists dedicated to rendering, but it became a bottleneck because time had to be booked with the few 3D visualizers trained in that software.

We now have established ways to do as much as we can in SketchUp, which is the fastest way. There isn’t a steep learning curve. Everybody can have it and everybody can use it to develop gorgeous renderings with extensions. We don’t need so many specialists. In Shanghai and Singapore, we use renderers such as Enscape. In India, we lean more toward CPU-based renderers, including SU Podium.

Charles: We also had a problem with third-party drawn perspectives. A designer would freestyle to make something look better. In this process, they might have a detailed understanding of what the interior would look like, but would often leave out the air vents, access panels, joint lines, and sprinklers because they thought they were ugly. Even worse, they would enlarge or shrink objects to give a false impression of what one would experience.

By transitioning to the VDC methodology, we ensure that perspectives remain true to life. We can also deliver beautiful renders instantly, so you can quickly look at things from a different point of view. There’s a nimbleness that is lost when creating perspectives with other workflows where the same limited views are updated over and over again.

Does your methodology transverse regions?

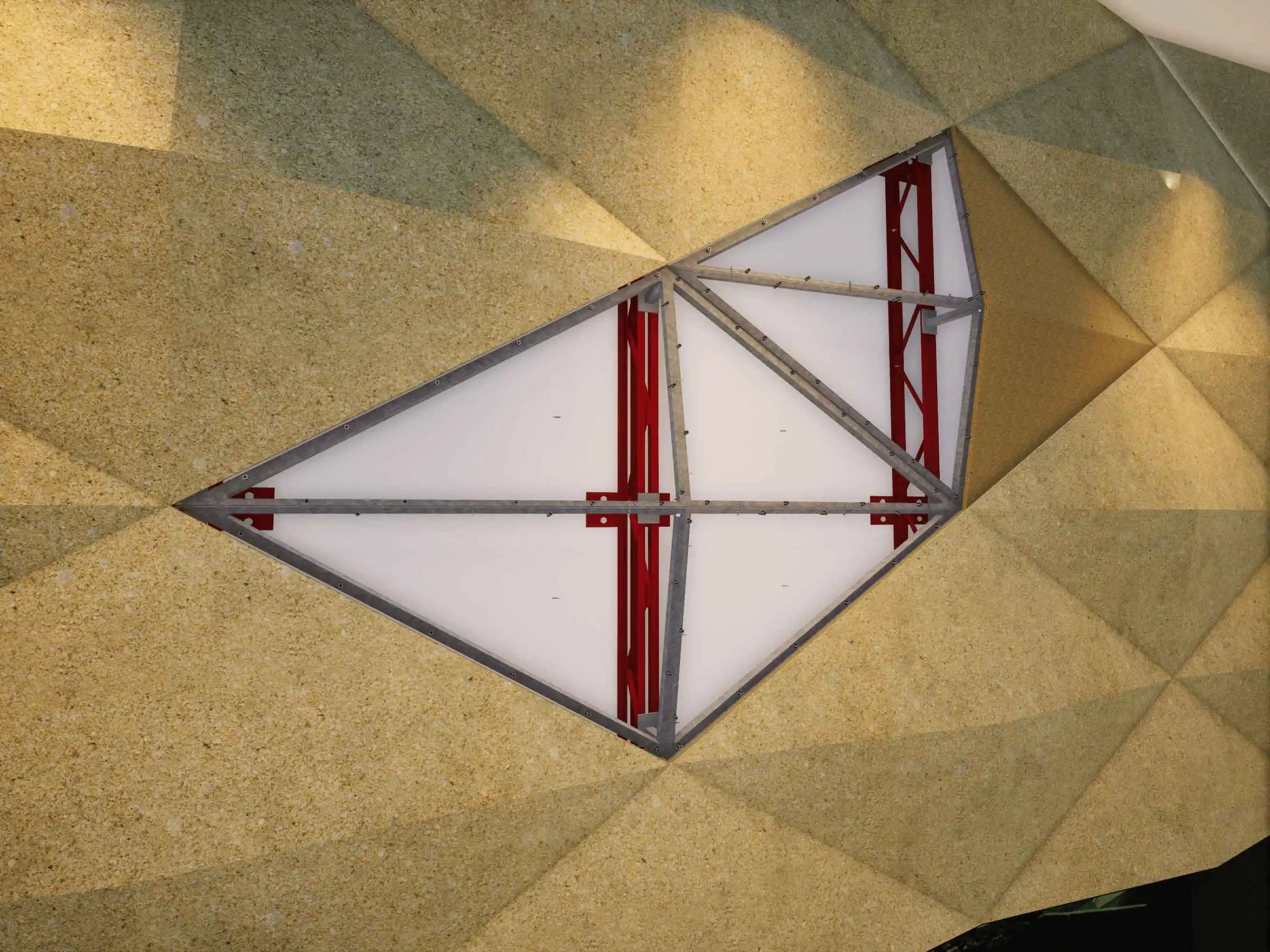

Charles: We developed our approach because we work with contractors trained in very different ways and to some extent that continues today. However, we think that the constructability aspect of VDC is applicable anywhere. There’s a great deal of value in being able to do virtual mock-ups and say, “Are you sure this is what you want? Because look here, this could be improved.”

“Constructible models eliminate wasted resource and materials and allow for an unprecedented attention to detail before reaching the site.”

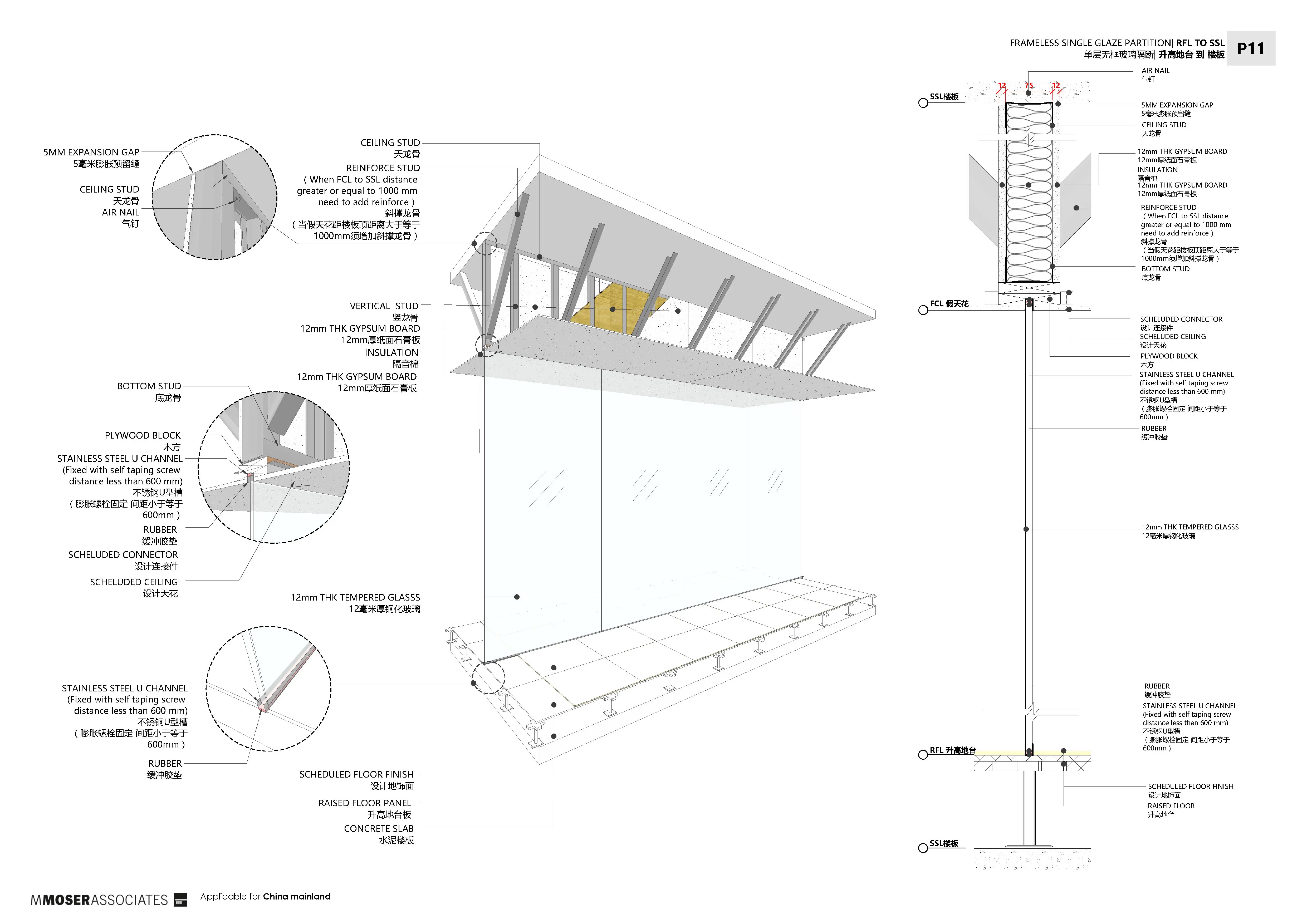

If you think of everything in a project as separate systems that must come together, there’s a huge amount of coordination required in what was traditionally called the design development stage. We now choose to call this integrated development because we are essentially combining the power, lighting, partition, and furniture systems.

The integrated development stage is where much of the change occurs and decisions are made. Documentation for the record is memorializing what we had agreed during all this collaborative effort. Documents may be still necessary for now but they record what was already worked out and understood by all and don’t serve to gain that agreement. That was done through a highly constructible model—a virtual construction.

About M Moser Associates

M Moser Associates has specialized in the design and delivery of workplace environments since 1981, with clients from the corporate, private healthcare, and education sectors. With over 900 staff in 16 offices on three continents, the company provides a holistic approach to physical and digital workplace environments of all scales.